Hidden

Images

Oct 9

021

Were

they saving on canvases?

Were

they concealing their mistakes?

Or

are all their paintings unfinished,

the

great works of art

we

admire and emulate

merely

rough drafts,

practice

pieces

from

apprentices' hands

waiting

to be painted over?

Beneath

my poems

there

are also hidden images

no

one will read

and

no technology recover.

All

the drafts

vanished

into the ether.

The

world

as

only I have seen it.

And

if not the life lived

then

the one I would have wished for.

What

a reader may not know

is

that a poem's never finished.

There's

the critical rereading,

tweaking

and tinkering,

second-guessing

regrets.

The

one I write later

that's

says the same

but

does it much better.

And

the fact it can't exist

until

it's been read.

Because

when a poem is put out into the world

you

must let it go,

like

a grown child

who

leaves the nest

and

begins a life of her own.

You

give it to the reader

and

it is transformed,

no

matter what you intended

or

might have hoped.

Who

will peer beneath its surface

and

scrape at its paint.

Who

will lift the canvas from its frame

and

see what's concealed.

Who

will expose it to light

and

scrutinize its phrases,

and

whose X ray mind

will

penetrate its layers.

Or

who will give it time

to

play in her head

as

she goes about her day,

unaware

of its presence.

Only

to re-emerge unexpectedly

in

a singular moment

of

clarity

meaning

delight.

This poem was inspired by this article

(see below). Treasures such as this, hidden beneath iconic paintings,

are being repeatedly discovered. And if they are not treasures

aesthetically, at least they may be as history and biography. But

this does not just occur in the visual arts . . .even though other

forms of art may not preserve them as well.

I think this phenomenon offers a

healthy insight into the artistic temperament and enterprise. That a

piece isn't conjured up out of nothing, but rests on a foundation of

previous work. That even though it's been sent out into the world, it

may still not fully satisfy the artist's eye or ear. That the

creation of art is an iterative process, so that what we regard as a

masterpiece was not necessarily finished, but rather part of an

ongoing work that was simply, for some reason, arrested in time. And,

of course, that a piece does not stand on its own: it must be seen,

read, heard, felt, consumed. Otherwise, like the tree that falls in

the forest unheard, it doesn't exist.

I'm no Picasso, however. And my rough

drafts are not preserved in long-dried paint. They are gone for good,

crumpled in a garbage bin or lost in cyberspace.

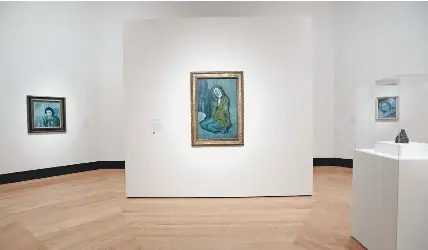

Picasso

exhibit at the AGO reveals what is hidden underneath his early

paintings

FRED

LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL/© PICASSO ESTATE/SOCAN (2021)

FRED

LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL/© PICASSO ESTATE/SOCAN (2021)

For

the Art Gallery of Ontario’s new exhibition of Pablo Picasso’s

art, testing was done on three of his early paintings using X-rays,

paint analysis and digital ‘false colour’ images, revealing

compositions hidden beneath the final works.

New

exhibit at the Art Gallery of Ontario showcases the painter’s focus

on sex, poverty during his Blue Period

When

curators, conservators and scientists subjected an early nude by

Pablo Picasso to a battery of tests, they found another painting

underneath, featuring a pensive man in evening dress. With its

rumpled bedsheets and dawning light, Picasso’s scene of a naked

woman scrubbing her leg represents the morning after in a brothel,

but the artist had painted it over a scene from the night before. So,

an image of a vulnerable woman covers one of a privileged man, an

effect replacing a cause.

Picasso:

Painting the Blue Period, a new exhibition at the Art Gallery of

Ontario, proves that what is covered up on a canvas can be as

important as what is shown – and reveals a youth from Catholic

Barcelona negotiating his attitudes toward women in libertine Paris.

The

backbone of this exhibition, finally opening after a 15month pandemic

delay, is the testing that the AGO and its coorganizer, the Phillips

Collection in Washington, have done on three paintings from Picasso’s

early career when he was trying to establish himself in Paris. Using

X-rays, paint analysis and digital “false colour” images that

highlight certain areas, the tests reveal compositions hidden

underneath the final paintings.

Under

The Blue Room (the 1901 nude from the Phillips), it’s the man in

evening dress, his pose allowing curators to conclude he was also

painted by Picasso. Under the AGO’s Crouching Beggarwoman of 1902,

there’s a scene from a park in Barcelona – but Kenneth Brummel,

the AGO curator responsible for the show, argues that the landscape

is too conservative to match up with Picasso’s temporary return to

Barcelona in 1902. The impoverished artist was probably reusing

somebody else’s canvas, although he borrowed the contour of hills

to create the outline of the woman’s cloak.

Testing

The Soup, a small 1902 painting in the AGO collection showing a bowed

woman offering a bowl to a child, the researchers discovered how

Picasso gradually simplified the composition to these two timeless

figures. The painting may have originally featured a second child, or

people eating at a table, in a less stylized image of poverty.

These

revelations are the foundation for a large show – more than 100

works, 94 of them by Picasso himself – that explains the artist’s

sources and techniques in his Blue Period, named for the limited

palette of melancholy blues he favoured between 1901-1906.

The

exhibition begins before he went blue, however, with the portraits

and nudes heavily influenced by the artists he had now encountered in

Paris: Edgar Degas and Henri de ToulouseLautrec. The Blue Room is

prefaced by a gallery full of cruder nudes as Picasso (then a mere

19-year-old) searched about for the right tone to depict the

moreor-less joyous sex-trade workers, entertainers and models of

Montmartre. The powerful Jeanne is seen foreshortened as though the

viewer stood at the foot of her bed buttoning his trousers; the

repellant Nude with Cats crouches in a pose that mimics the animals.

Does

Picasso sympathize with these women, or lust after them? A bit of

both, since he also shows himself in a small self-portrait as another

gentleman in evening dress with a top hat – and surrounded by

bare-breasted ladies of the night.

But

in 1901, he was also introduced to the women of the SaintLazare

hospital prison, where he began mournful blue paintings such as Woman

Ironing or Melancholy Woman. Not surprisingly, despite their deep

humanity, these depressive figures didn’t sell well, and Picasso

was forced home again. As he transported his new style back to Spain

in 1902, its religiosity becomes apparent: Blue is the colour of the

Virgin’s cloak after all. Curators Brummel and his Phillips

colleague Susan Behrends Frank include a particularly melodramatic

Our Lady of Sorrows by the 16th-century Spanish Luis de Morales to

remind you of that.

Now,

Picasso’s paintings all feature clothed women, beggars and single

mothers, the downtrodden elevated through their visual association

with religious art. Even two sex-trade workers, seen from behind in

Two Women at a Bar, are clothed – and closed off to the viewer’s

consuming eye as they turn their backs.

Here,

the curators reveal how Picasso dignifies the woman by comparing that

painting to a small version of Augustin Rodin’s famed Thinker, with

its similar emphasis on the musculature of a turned back. The woman

and child in The Soup, meanwhile, are compared to Pierre Puvis de

Chavanne’s symbolic representations of the figure of Charity and

Honoré Daumier’s drawing of a famished couple at a table, the

woman baring a great breast to her baby while she devours her food.

The notion that feeding one’s own child represents an act of

charity is certainly the conceit of male artists, not nursing

mothers, but Picasso elevates Daumier’s grittier vision of hunger

to something classically respectful of its subjects.

The

curators don’t position their work this way, but viewers may be

forgiven if, by this point, they recognize Painting the Blue Period

as an exhibition of whores and madonnas: A few impoverished blue men

only begin to appear in the final room. (They include the

particularly fine Portrait of a Man, a person Picasso described as “a

sort of madman who was a well-known figure in Barcelona.”) The

young and socially engaged Picasso feels for the women of the street

and the tenement. Considering the notorious misogyny of the artist’s

later biography, it’s easy – with hindsight – to conclude that

the artist who would paint Guernica was one of those people who was

better at loving humanity than at loving individuals.

Not

coincidentally, as Fernande Olivier, his first live-in girlfriend,

appears on the scene, Picasso moves into the Pink Period in 1906 and

begins painting nudes once again. As a footnote, there’s a room

full of them here, many based on Olivier herself, their warm skin,

auburn hair and pink or beige backdrops celebrating love and life.

One, Nude Combing Her Hair, begins to show the reduction of the body

to geometric planes. A year later, Picasso would paint the

proto-cubist group portrait Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, a

representation of the brothel’s workers as wild, exotic and

frightening. The rest is art history.